Expo

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

Clinical Chem.Molecular DiagnosticsHematologyImmunologyMicrobiologyPathologyTechnologyIndustry

Events

Webinars

- New Blood Test Index Offers Earlier Detection of Liver Scarring

- Electronic Nose Smells Early Signs of Ovarian Cancer in Blood

- Simple Blood Test Offers New Path to Alzheimer’s Assessment in Primary Care

- Existing Hospital Analyzers Can Identify Fake Liquid Medical Products

- Rapid Blood Testing Method Aids Safer Decision-Making in Drug-Related Emergencies

- AI-Powered Blood Test Flags Relapse Risk Earlier After Transplant

- World’s First Portable POC Test Simultaneously Detects Four Common STIs in One Hour

- Simple One-Hour Saliva Test Detects Common Cancers

- Blood Test Could Help Guide Treatment Decisions in Germ Cell Tumors

- Blood Test Could Spot Common Post-Surgery Condition Early

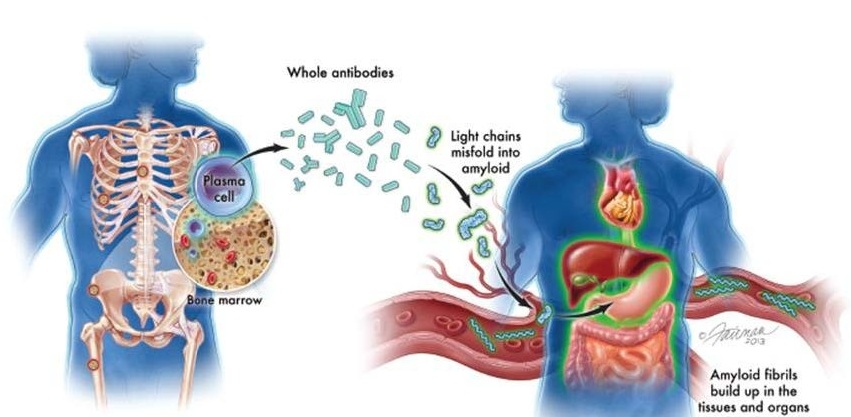

- New Guidelines Aim to Improve AL Amyloidosis Diagnosis

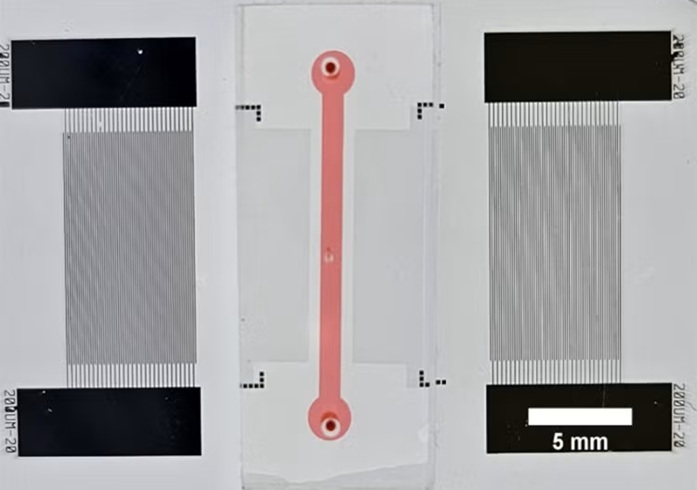

- Fast and Easy Test Could Revolutionize Blood Transfusions

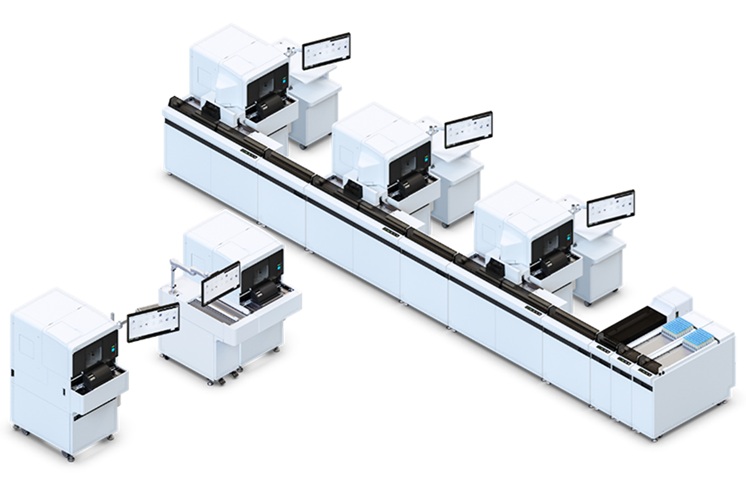

- Automated Hemostasis System Helps Labs of All Sizes Optimize Workflow

- High-Sensitivity Blood Test Improves Assessment of Clotting Risk in Heart Disease Patients

- AI Algorithm Effectively Distinguishes Alpha Thalassemia Subtypes

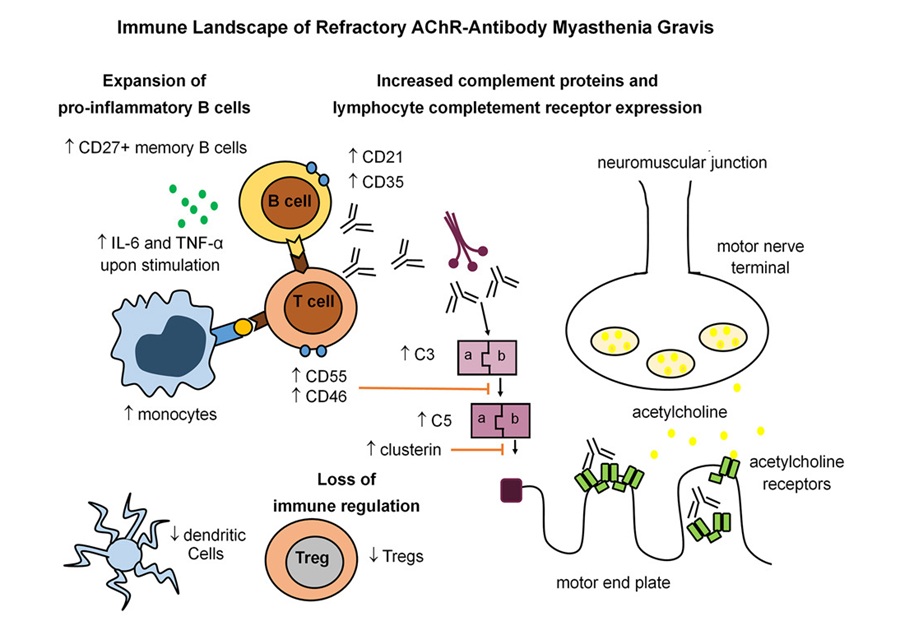

- Immune Signature Identified in Treatment-Resistant Myasthenia Gravis

- New Biomarker Predicts Chemotherapy Response in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

- Blood Test Identifies Lung Cancer Patients Who Can Benefit from Immunotherapy Drug

- Whole-Genome Sequencing Approach Identifies Cancer Patients Benefitting From PARP-Inhibitor Treatment

- Ultrasensitive Liquid Biopsy Demonstrates Efficacy in Predicting Immunotherapy Response

- AI-Driven Diagnostic Demonstrates High Accuracy in Detecting Periprosthetic Joint Infection

- Blood Test “Clocks” Predict Start of Alzheimer’s Symptoms

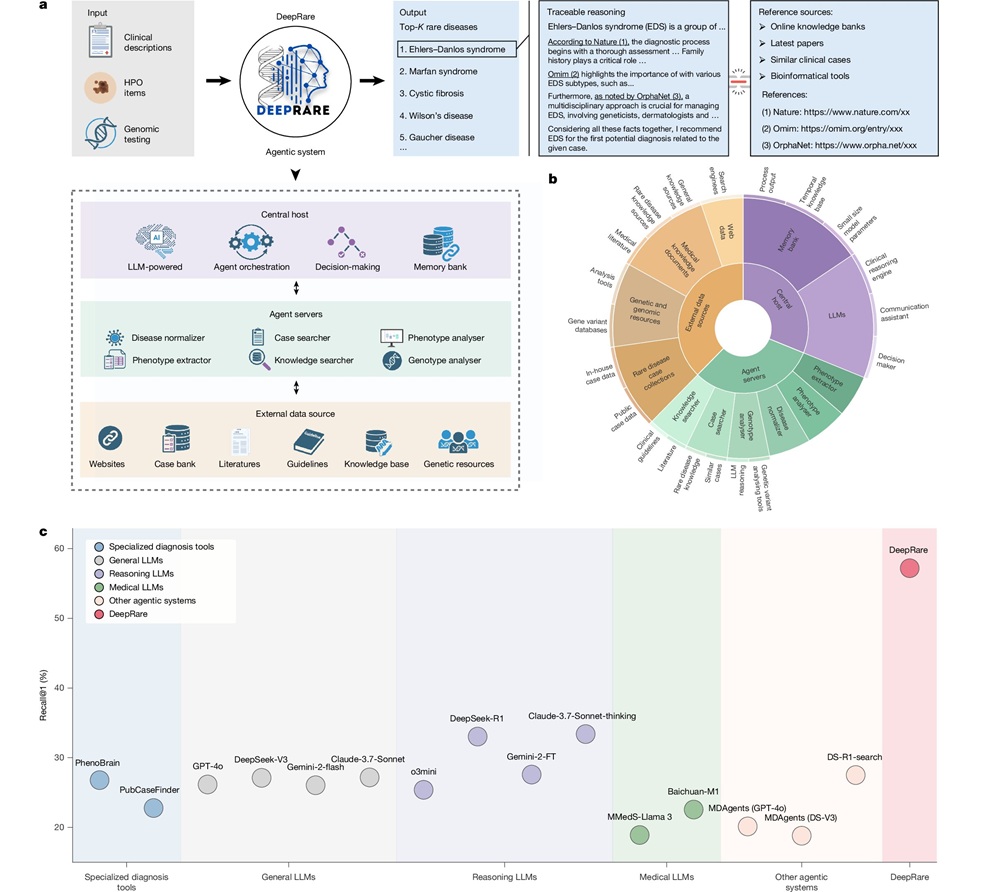

- AI-Powered Biomarker Predicts Liver Cancer Risk

- Robotic Technology Unveiled for Automated Diagnostic Blood Draws

- ADLM Launches First-of-Its-Kind Data Science Program for Laboratory Medicine Professionals

- Cepheid Joins CDC Initiative to Strengthen U.S. Pandemic Testing Preparednesss

- QuidelOrtho Collaborates with Lifotronic to Expand Global Immunoassay Portfolio

- WHX Labs in Dubai spotlights leadership skills shaping next-generation laboratories

- New Collaboration Brings Automated Mass Spectrometry to Routine Laboratory Testing

- AI-Powered Cervical Cancer Test Set for Major Rollout in Latin America

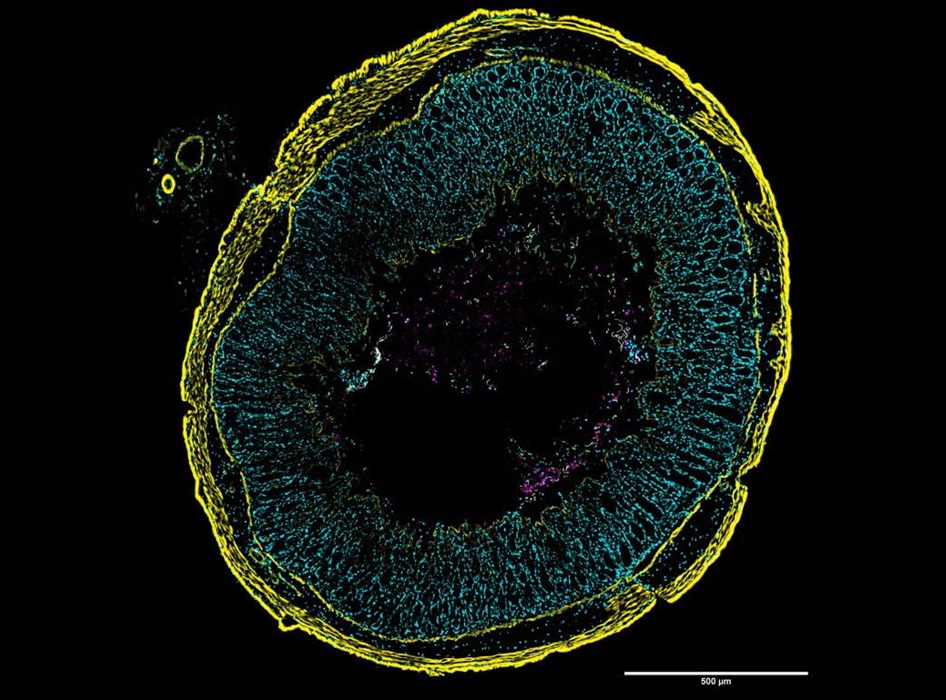

- Barcoded DNA Sheds Light on Hidden Complexities in Breast Cancer Detection

- CRISPR-Based Platform Pinpoints Drivers of Acute Myeloid Leukemia in Patient Cells

- Protective Brain Protein Emerges as Biomarker Target in Alzheimer’s Disease

- Genome Analysis Predicts Likelihood of Neurodisability in Oxygen-Deprived Newborns

- Gene Panel Predicts Disease Progession for Patients with B-cell Lymphoma

- Sex Differences in Alzheimer’s Biomarkers Linked to Faster Cognitive Decline

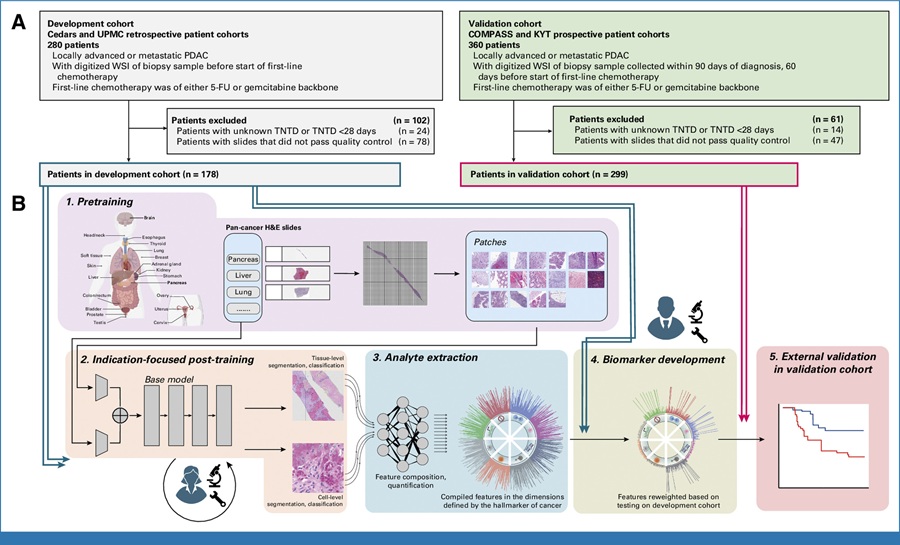

- AI Tool Predicts Chemotherapy Response from Biopsy Slides

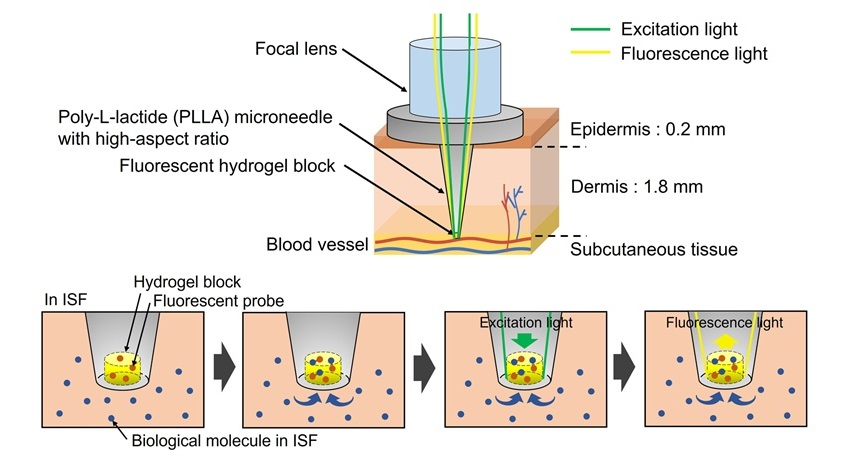

- World’s First Optical Microneedle Device to Enable Blood-Sampling-Free Clinical Testing

- Pathogen-Agnostic Testing Reveals Hidden Respiratory Threats in Negative Samples

- Molecular Imaging to Reduce Need for Melanoma Biopsies

Expo

Expo

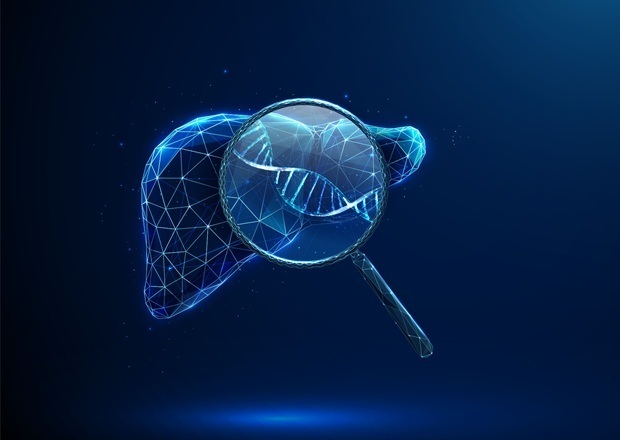

- New Blood Test Index Offers Earlier Detection of Liver Scarring

- Electronic Nose Smells Early Signs of Ovarian Cancer in Blood

- Simple Blood Test Offers New Path to Alzheimer’s Assessment in Primary Care

- Existing Hospital Analyzers Can Identify Fake Liquid Medical Products

- Rapid Blood Testing Method Aids Safer Decision-Making in Drug-Related Emergencies

- AI-Powered Blood Test Flags Relapse Risk Earlier After Transplant

- World’s First Portable POC Test Simultaneously Detects Four Common STIs in One Hour

- Simple One-Hour Saliva Test Detects Common Cancers

- Blood Test Could Help Guide Treatment Decisions in Germ Cell Tumors

- Blood Test Could Spot Common Post-Surgery Condition Early

- New Guidelines Aim to Improve AL Amyloidosis Diagnosis

- Fast and Easy Test Could Revolutionize Blood Transfusions

- Automated Hemostasis System Helps Labs of All Sizes Optimize Workflow

- High-Sensitivity Blood Test Improves Assessment of Clotting Risk in Heart Disease Patients

- AI Algorithm Effectively Distinguishes Alpha Thalassemia Subtypes

- Immune Signature Identified in Treatment-Resistant Myasthenia Gravis

- New Biomarker Predicts Chemotherapy Response in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

- Blood Test Identifies Lung Cancer Patients Who Can Benefit from Immunotherapy Drug

- Whole-Genome Sequencing Approach Identifies Cancer Patients Benefitting From PARP-Inhibitor Treatment

- Ultrasensitive Liquid Biopsy Demonstrates Efficacy in Predicting Immunotherapy Response

- AI-Driven Diagnostic Demonstrates High Accuracy in Detecting Periprosthetic Joint Infection

- Blood Test “Clocks” Predict Start of Alzheimer’s Symptoms

- AI-Powered Biomarker Predicts Liver Cancer Risk

- Robotic Technology Unveiled for Automated Diagnostic Blood Draws

- ADLM Launches First-of-Its-Kind Data Science Program for Laboratory Medicine Professionals

- Cepheid Joins CDC Initiative to Strengthen U.S. Pandemic Testing Preparednesss

- QuidelOrtho Collaborates with Lifotronic to Expand Global Immunoassay Portfolio

- WHX Labs in Dubai spotlights leadership skills shaping next-generation laboratories

- New Collaboration Brings Automated Mass Spectrometry to Routine Laboratory Testing

- AI-Powered Cervical Cancer Test Set for Major Rollout in Latin America

- Barcoded DNA Sheds Light on Hidden Complexities in Breast Cancer Detection

- CRISPR-Based Platform Pinpoints Drivers of Acute Myeloid Leukemia in Patient Cells

- Protective Brain Protein Emerges as Biomarker Target in Alzheimer’s Disease

- Genome Analysis Predicts Likelihood of Neurodisability in Oxygen-Deprived Newborns

- Gene Panel Predicts Disease Progession for Patients with B-cell Lymphoma

- Sex Differences in Alzheimer’s Biomarkers Linked to Faster Cognitive Decline

- AI Tool Predicts Chemotherapy Response from Biopsy Slides

- World’s First Optical Microneedle Device to Enable Blood-Sampling-Free Clinical Testing

- Pathogen-Agnostic Testing Reveals Hidden Respiratory Threats in Negative Samples

- Molecular Imaging to Reduce Need for Melanoma Biopsies