Expo

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

Clinical Chem.Molecular DiagnosticsHematologyImmunology

PathologyTechnologyIndustry

Events

Webinars

- Electronic Nose Smells Early Signs of Ovarian Cancer in Blood

- Simple Blood Test Offers New Path to Alzheimer’s Assessment in Primary Care

- Existing Hospital Analyzers Can Identify Fake Liquid Medical Products

- Rapid Blood Testing Method Aids Safer Decision-Making in Drug-Related Emergencies

- New PSA-Based Prognostic Model Improves Prostate Cancer Risk Assessment

- Blood Test Predicts Which Bladder Cancer Patients May Safely Skip Surgery

- Ultra-Sensitive DNA Test Identifies Relapse Risk in Aggressive Leukemia

- Blood Test Could Help Detect Gallbladder Cancer Earlier

- New Blood Test Score Detects Hidden Alcohol-Related Liver Disease

- New Blood Test Predicts Who Will Most Likely Live Longer

- New Guidelines Aim to Improve AL Amyloidosis Diagnosis

- Fast and Easy Test Could Revolutionize Blood Transfusions

- Automated Hemostasis System Helps Labs of All Sizes Optimize Workflow

- High-Sensitivity Blood Test Improves Assessment of Clotting Risk in Heart Disease Patients

- AI Algorithm Effectively Distinguishes Alpha Thalassemia Subtypes

- Blood Test Identifies Lung Cancer Patients Who Can Benefit from Immunotherapy Drug

- Whole-Genome Sequencing Approach Identifies Cancer Patients Benefitting From PARP-Inhibitor Treatment

- Ultrasensitive Liquid Biopsy Demonstrates Efficacy in Predicting Immunotherapy Response

- Blood Test Could Identify Colon Cancer Patients to Benefit from NSAIDs

- Blood Test Could Detect Adverse Immunotherapy Effects

- Hidden Gut Viruses Linked to Colorectal Cancer Risk

- Three-Test Panel Launched for Detection of Liver Fluke Infections

- Rapid Test Promises Faster Answers for Drug-Resistant Infections

- CRISPR-Based Technology Neutralizes Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria

- Comprehensive Review Identifies Gut Microbiome Signatures Associated With Alzheimer’s Disease

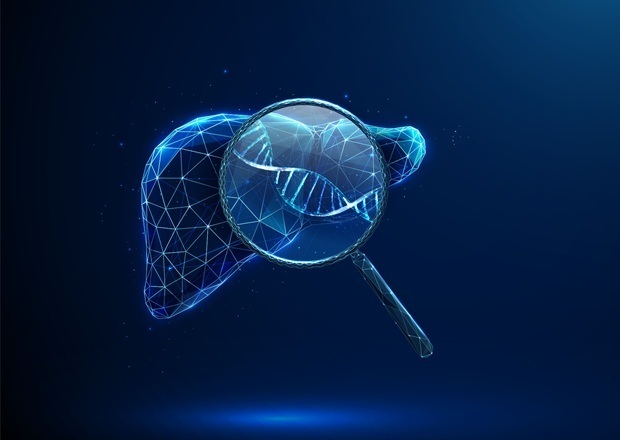

- AI-Powered Biomarker Predicts Liver Cancer Risk

- Robotic Technology Unveiled for Automated Diagnostic Blood Draws

- ADLM Launches First-of-Its-Kind Data Science Program for Laboratory Medicine Professionals

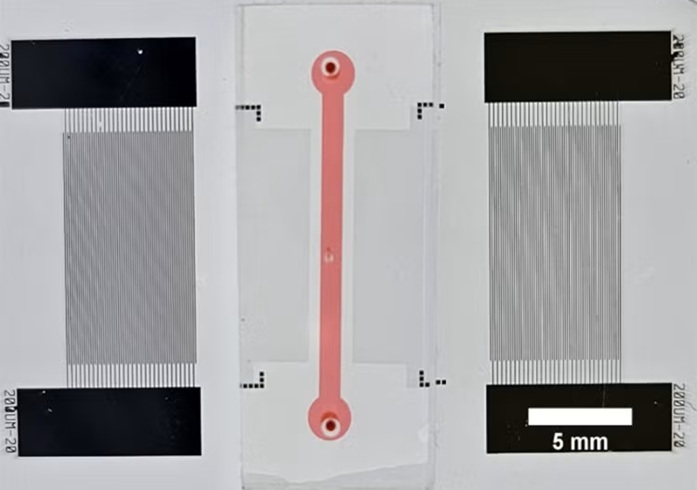

- Aptamer Biosensor Technology to Transform Virus Detection

- AI Models Could Predict Pre-Eclampsia and Anemia Earlier Using Routine Blood Tests

- QuidelOrtho Collaborates with Lifotronic to Expand Global Immunoassay Portfolio

- WHX Labs in Dubai spotlights leadership skills shaping next-generation laboratories

- New Collaboration Brings Automated Mass Spectrometry to Routine Laboratory Testing

- AI-Powered Cervical Cancer Test Set for Major Rollout in Latin America

- Diasorin and Fisher Scientific Enter into US Distribution Agreement for Molecular POC Platform

- Protective Brain Protein Emerges as Biomarker Target in Alzheimer’s Disease

- Genome Analysis Predicts Likelihood of Neurodisability in Oxygen-Deprived Newborns

- Gene Panel Predicts Disease Progession for Patients with B-cell Lymphoma

- New Method Simplifies Preparation of Tumor Genomic DNA Libraries

- New Tool Developed for Diagnosis of Chronic HBV Infection

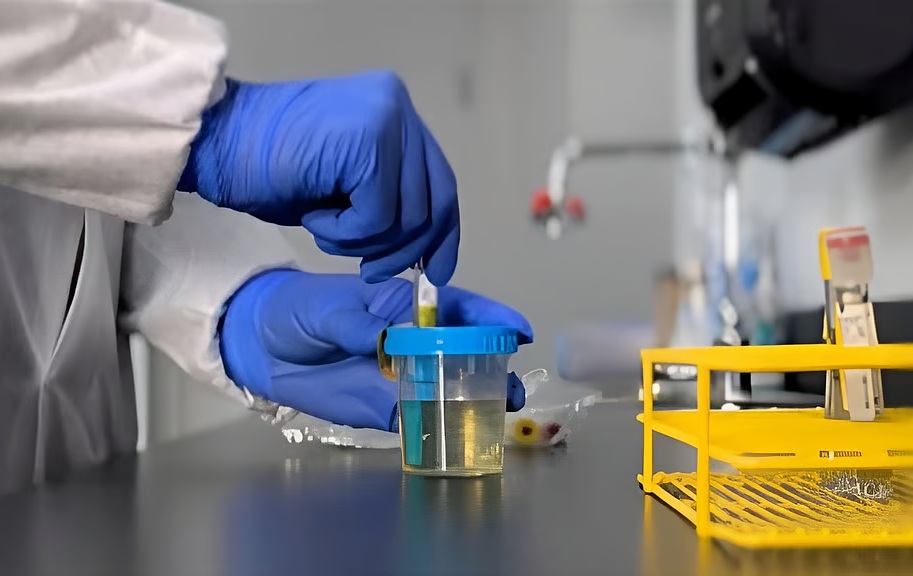

- Urine Specimen Collection System Improves Diagnostic Accuracy and Efficiency

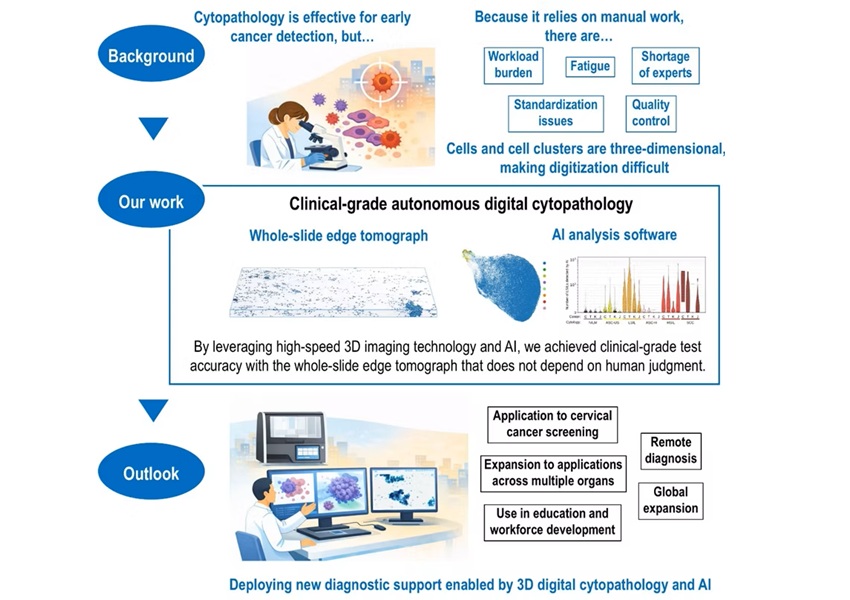

- AI-Powered 3D Scanning System Speeds Cancer Screening

- Single Sample Classifier Predicts Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Subtypes in Patient Samples

- New AI-Driven Platform Standardizes Tuberculosis Smear Microscopy Workflow

- AI Tool Uses Blood Biomarkers to Predict Transplant Complications Before Symptoms Appear

Expo

Expo

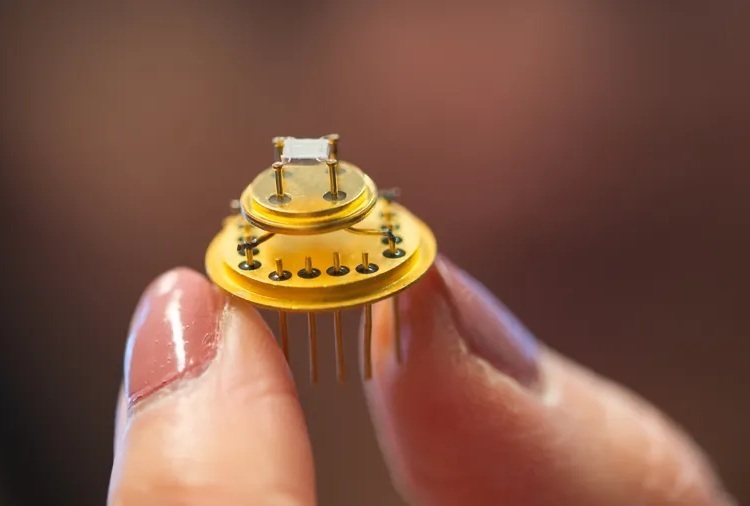

- Electronic Nose Smells Early Signs of Ovarian Cancer in Blood

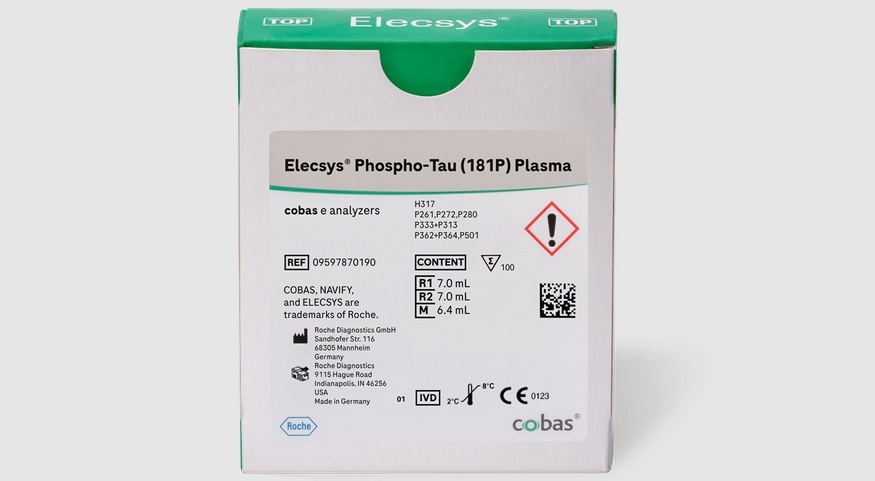

- Simple Blood Test Offers New Path to Alzheimer’s Assessment in Primary Care

- Existing Hospital Analyzers Can Identify Fake Liquid Medical Products

- Rapid Blood Testing Method Aids Safer Decision-Making in Drug-Related Emergencies

- New PSA-Based Prognostic Model Improves Prostate Cancer Risk Assessment

- Blood Test Predicts Which Bladder Cancer Patients May Safely Skip Surgery

- Ultra-Sensitive DNA Test Identifies Relapse Risk in Aggressive Leukemia

- Blood Test Could Help Detect Gallbladder Cancer Earlier

- New Blood Test Score Detects Hidden Alcohol-Related Liver Disease

- New Blood Test Predicts Who Will Most Likely Live Longer

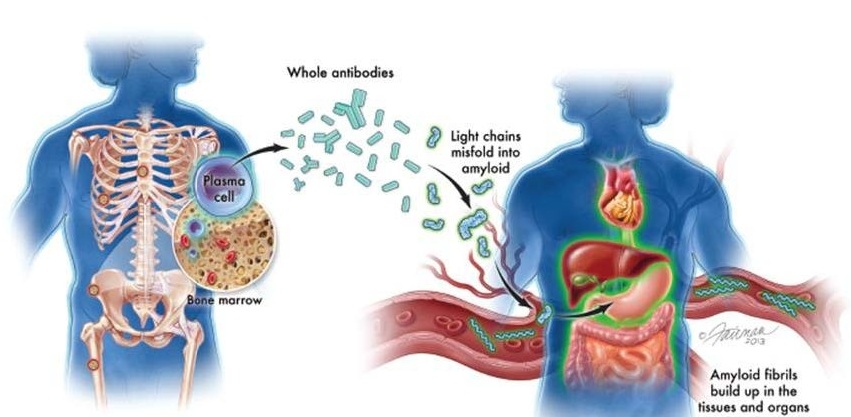

- New Guidelines Aim to Improve AL Amyloidosis Diagnosis

- Fast and Easy Test Could Revolutionize Blood Transfusions

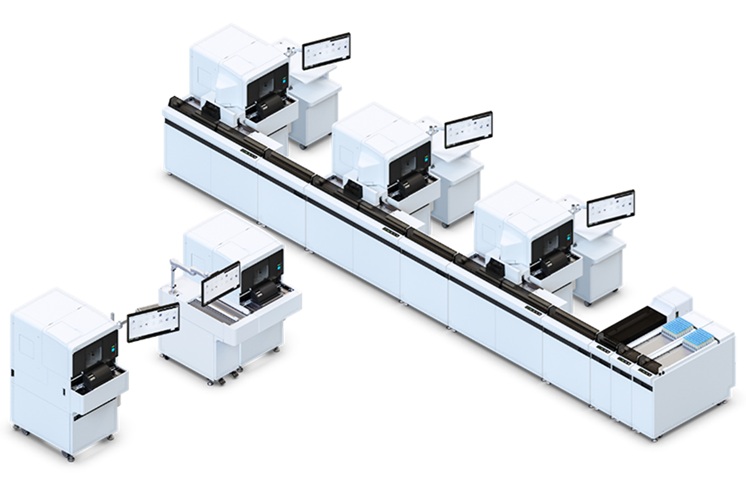

- Automated Hemostasis System Helps Labs of All Sizes Optimize Workflow

- High-Sensitivity Blood Test Improves Assessment of Clotting Risk in Heart Disease Patients

- AI Algorithm Effectively Distinguishes Alpha Thalassemia Subtypes

- Blood Test Identifies Lung Cancer Patients Who Can Benefit from Immunotherapy Drug

- Whole-Genome Sequencing Approach Identifies Cancer Patients Benefitting From PARP-Inhibitor Treatment

- Ultrasensitive Liquid Biopsy Demonstrates Efficacy in Predicting Immunotherapy Response

- Blood Test Could Identify Colon Cancer Patients to Benefit from NSAIDs

- Blood Test Could Detect Adverse Immunotherapy Effects

- Hidden Gut Viruses Linked to Colorectal Cancer Risk

- Three-Test Panel Launched for Detection of Liver Fluke Infections

- Rapid Test Promises Faster Answers for Drug-Resistant Infections

- CRISPR-Based Technology Neutralizes Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria

- Comprehensive Review Identifies Gut Microbiome Signatures Associated With Alzheimer’s Disease

- AI-Powered Biomarker Predicts Liver Cancer Risk

- Robotic Technology Unveiled for Automated Diagnostic Blood Draws

- ADLM Launches First-of-Its-Kind Data Science Program for Laboratory Medicine Professionals

- Aptamer Biosensor Technology to Transform Virus Detection

- AI Models Could Predict Pre-Eclampsia and Anemia Earlier Using Routine Blood Tests

- QuidelOrtho Collaborates with Lifotronic to Expand Global Immunoassay Portfolio

- WHX Labs in Dubai spotlights leadership skills shaping next-generation laboratories

- New Collaboration Brings Automated Mass Spectrometry to Routine Laboratory Testing

- AI-Powered Cervical Cancer Test Set for Major Rollout in Latin America

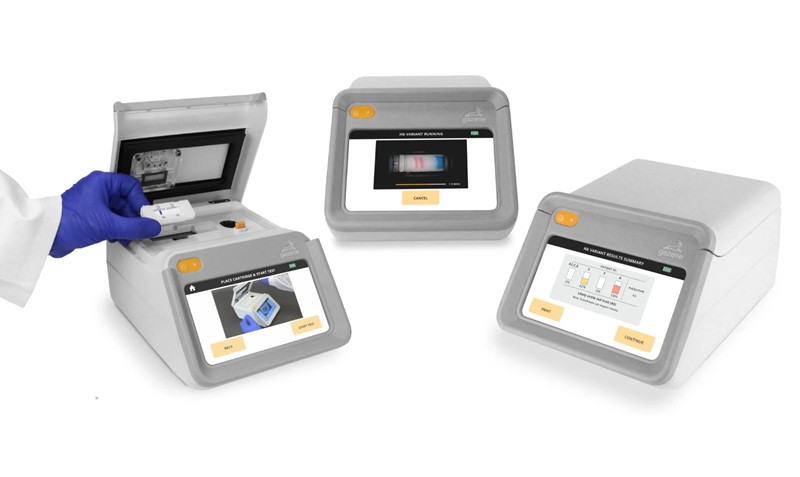

- Diasorin and Fisher Scientific Enter into US Distribution Agreement for Molecular POC Platform

- Protective Brain Protein Emerges as Biomarker Target in Alzheimer’s Disease

- Genome Analysis Predicts Likelihood of Neurodisability in Oxygen-Deprived Newborns

- Gene Panel Predicts Disease Progession for Patients with B-cell Lymphoma

- New Method Simplifies Preparation of Tumor Genomic DNA Libraries

- New Tool Developed for Diagnosis of Chronic HBV Infection

- Urine Specimen Collection System Improves Diagnostic Accuracy and Efficiency

- AI-Powered 3D Scanning System Speeds Cancer Screening

- Single Sample Classifier Predicts Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Subtypes in Patient Samples

- New AI-Driven Platform Standardizes Tuberculosis Smear Microscopy Workflow

- AI Tool Uses Blood Biomarkers to Predict Transplant Complications Before Symptoms Appear